BY SAEED NAQVI

It is nice to remember the 1946 – Royal Indian Navy Mutiny just a few days before we celebrate our Independence Day. It is not just a neglected event in the history of Independence but one that was suppressed equally by the colonial masters as well as by leaders of the Congress. In fact, the Congress remained so gripped by paranoia of the traumatic event that its government in Bengal as late as 1965 tried every trick in the book to stop Utpal Dutt’s “Kallol” (Storm), a play based on the mutiny, from being staged. Despite Congress obstructions, the play was staged at Minerva theatre to record audiences. Scholar Ashis Nandy, also in the audience, is a witness to its popularity. These are some of the layers to the unputdownable narrative Pramod Kapoor has woven around the historic event in a well researched book.

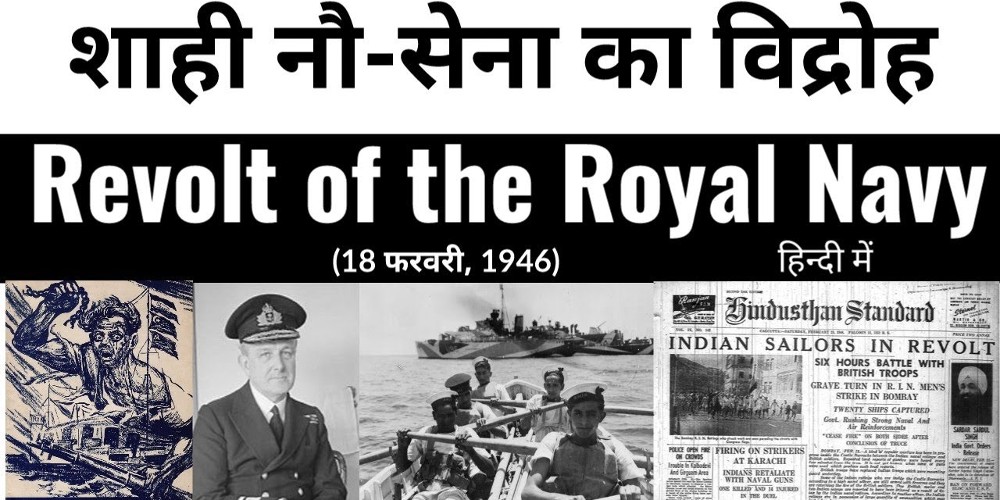

The Naval Mutiny of February 1946 was the greatest embarrassment the British faced. Britain, after all, boasted of an Admiralty. Britannia ruled the waves for nearly two centuries.

A riveting part of the book is the conspiracy before the spark was ignited by the “privates” (non commissioned officers) and sailors. Who were the politicians involved? Where did the conspirators meet? How did they escape British Intelligence consisting largely of “loyal” Indians?

In his advance praise for the book, film maker Shyam Benegal introduces a nugget about one Balai Dutt “barely out of his teens” among the Mutiny’s leaders. Later, Dutt, a staunch communist, rose to become an advertising executive in Lintas which Benegal joined as a copy writer. This is when Benegal read the Mutiny of the Innocents, Dutt’s insider account of the Mutiny, much before it was published. Popular historian William Dalrymple asks a pertinent question: “could 1946 have turned into a rerun of the Great Uprising of 1857?”

The book places something of a dampener, on the romantic image that many have nurtured of our national leaders – Gandhi, Nehru, Sardar Patel as “fighters” against the British. All of them appear to be more sympathetic to the British than to the ratings who had ignited a massive rebellion against discrimination and poor rations. It was a popular uprising against the British. Why was the Congress opposed to it?

What must have rung alarm bells in London and conservative Indians like Gandhi, Patel and Jinnah was the fact that the leadership of the uprising was with the Communist Party of India. Leaders like S.A. Dange, who later became Secretary General of the Party were in the vanguard as were leaders of the left wing of the Congress party like Aruna Asaf Ali. Nehru’s dilemma was acute. He was anxious about the left faction of the Congress: what if it deserts the party, thereby weakening him?

After extensive planning by the “plotters” (writes Kapoor) “the fuse was ignited on Monday, 18 February”. Kapoor extracts a quote from historian Sumit Sarakar’s Modern India: “the afternoon of 20 February saw remarkable scenes of fraternization, with crowds bringing food for the striking ratings at the Gateway of India and shop keepers inviting them to take whatever they needed.” And the Congress opposed this?

The mutiny spread to 78 ships, 21 shore establishments and over 20,000 ratings. “In less than 48 hours, it had crippled one of the most formidable navies of the Second World War. There were pitched battles. Hundreds were killed.”

It impacted severely on the leadership of the Congress and the Muslim League who were making cow eyes at the British as a matter of tactics. Freedom, they seemed to have reckoned, would come as a reward for good behaviour not by scaring the British – sinking their Armada, for instance.

On the opposite side was a mesmerizing, vocal galaxy: Prithviraj Kapoor, Salil Chowdhry, Balraj Sahni, Zohra Sehgal, Utpal Dutt, Aruna Asaf Ali, Minoo Musani, Ashoka Mehta, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Josh Malihabadi, Sahir Ludhianvi, and a host of others.

Hindustan Standard of 28 February has its page 1 cluttered with reactions of Congress leaders. Gandhi’s reaction is a banner across five columns.

Gandhi opposed Aruna Asaf Ali’s call: “I would rather unite Hindus and Muslims at the barricades, than on the constitutional front.” Gandhi’s response, “the barricade life has to be followed by the constitution.” According to Gandhi, Aruna “betrays want of foresight in disbelieving British declarations and precipitating a quarrel in anticipation.”

The same page has Maulana Azad, President of Congress, arguing that “the national spirit must not be suppressed.” Sardar Patel on the other hand is worried about “the mass awakening being exploited” by others.

Who are the “others”? This is the crux of the matter.

That the Navy, the pride of Britannia, was so vulnerable was disconcerting enough. What really set the cat among the pigeons in Westminster was the rapid gains being made by the communists in India and globally.

Although the Telengana uprising occupied newspaper headlines only in July 1946, intelligence reports on the massive underground network was available to the British much earlier. Beyond India Mao’s long march was in its final stages when mutiny erupted in the Navy.

In the 40s and the 50s, just as colonialism was receding, Imperialism was being challenged by communist expansion in Korea particularly after China crossed the Yalu river in 1950. In 1957, the first communist government through the ballot box was installed in Kerala. These events happened later but the Imperial establishment had sensed the wind blowing in one direction.

As soon as the mutiny expanded, Clement Atlee’s government in London, dispatched the Cabinet Mission, replaced Lord Wavel by Lord Mountbatten, set 30 June1948 as final date for independence.

Mountbatten brought the date forward to August 15. Mountbatten swiftly grasped the message from London: hand over power to leaders the British had cultivated, leaders who were “people like us”. Considering the left wave sweeping the world since the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, there was every danger of the ground being cut from under feet of the “moderate” politicians in India the British had struck a rapport with.

(Saeed Naqvi is a senior Indian journalist, television commentator, interviewer, and a Distinguished Fellow at Observer Research Foundation. Mr. Naqvi is also a mentor and a guest blogger with Canary Trap)

Canary Trap is on Telegram. Click here to join CT’s Telegram channel and stay updated with insightful and in-depth content on Security, Intelligence, Politics, and Tech.