BY VK SHASHIKUMAR

India is in the midst of a severe economic contraction. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecast India’s GDP (Gross Domestic Products) growth rate at 1.9 per cent in fiscal year 2020-21, the lowest in the last four decades. IMF’s World Economic Outlook paints a bleak prognosis of Covid19 hit world economy, which it says will decelerate 3%.

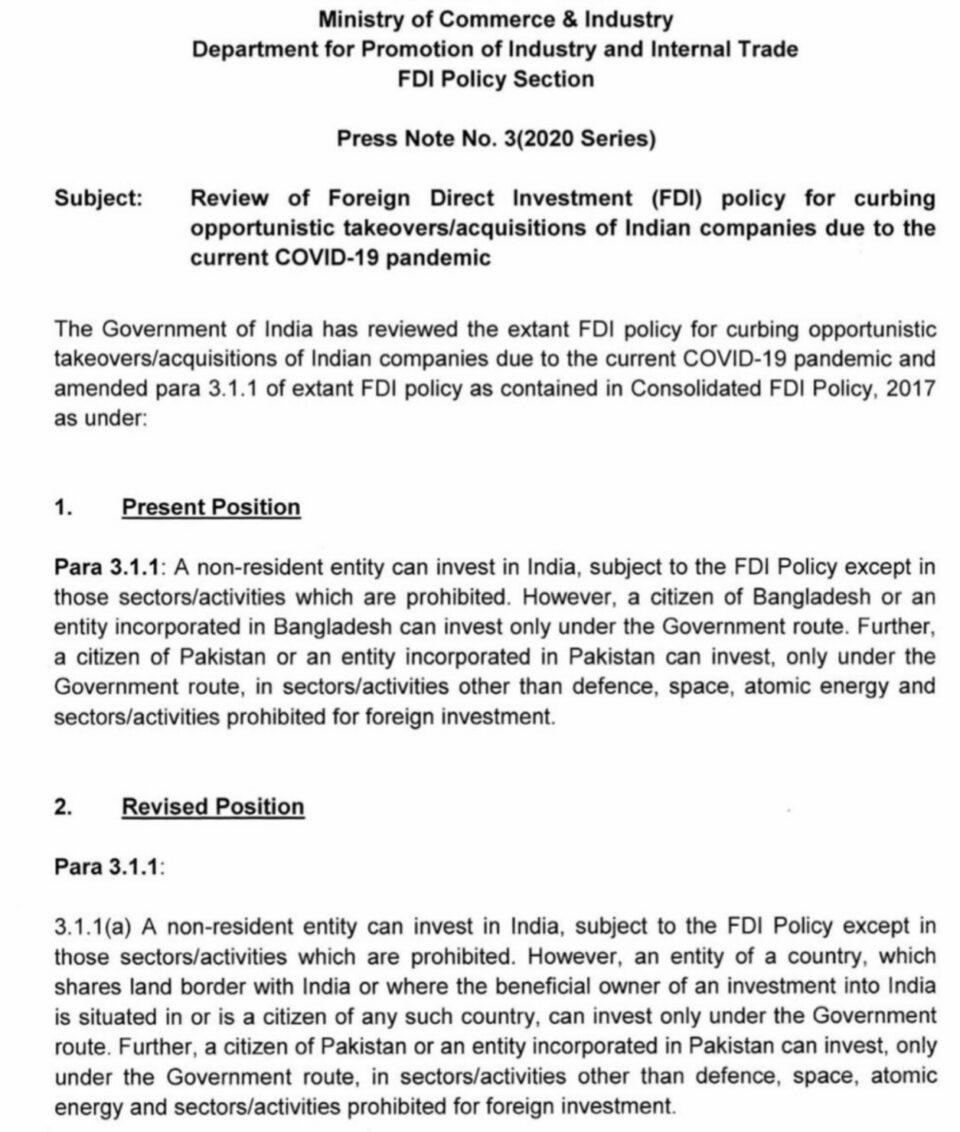

Four days after IMF’s Economic Counsellor, Gita Gopinath, outlined the possibility of the global economy experiencing its worst recession since the Great Depression, the Government of India (GoI) imposed takeover curbs on China. A GoI policy guidance issued on April 18 stated: “An entity of country, which shares land border with India or where the beneficial owner of an investment into India is situated in or is a citizen of any such country, can invest only under the Government route.”

This effectively means that the GoI has imposed curbs on opportunistic takeovers/acquisitions of Indian companies as the Indian economy goes into a tailspin because of the Covid19 pandemic. But why is GoI worried about opportunistic takeover of Indian companies by Chinese investments?

Stealth Investment In Tech Enabled Start-Ups:

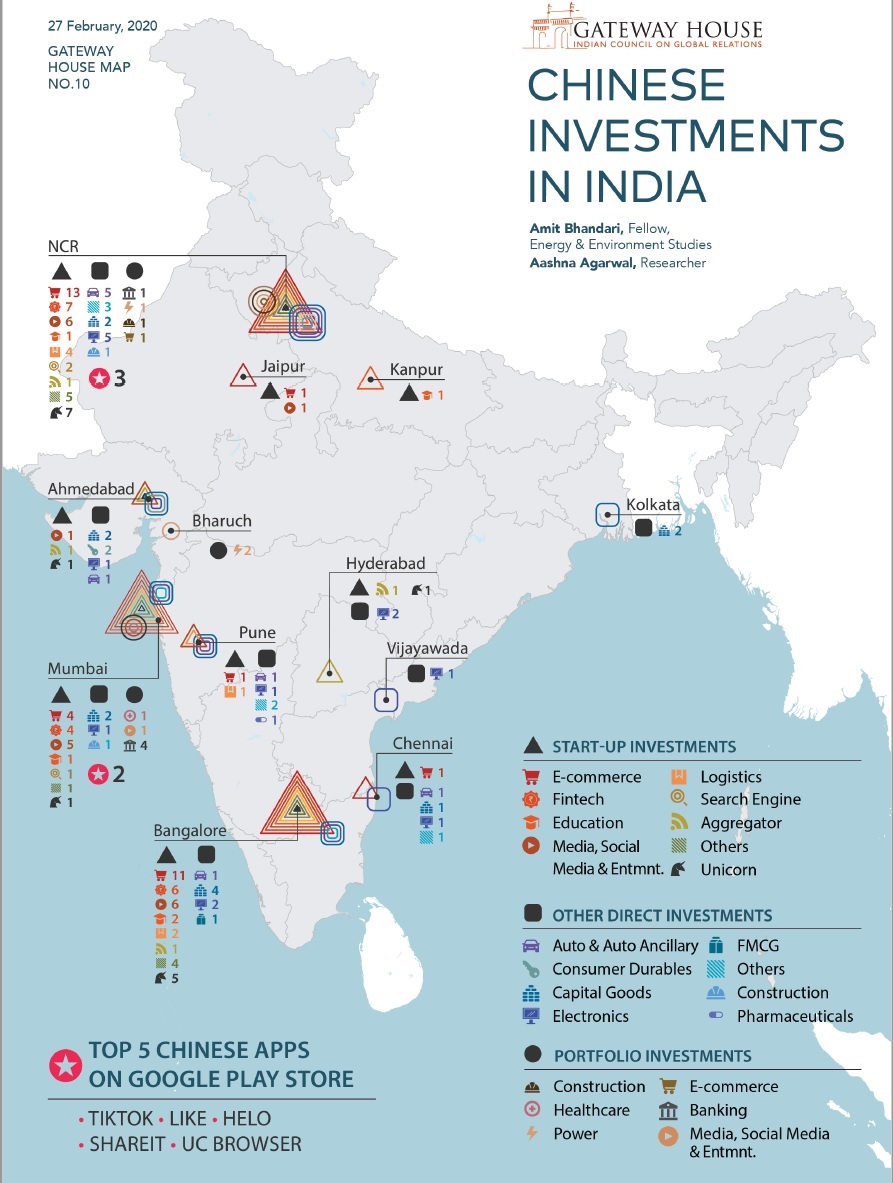

The Chinese investment strategy in India over the last five years has focused on grabbing significant chunks of technology enabled start-ups. Chinese venture funds are often routed to India through its entities located in Singapore, Hong Kong, Mauritius and so on. For example, Alibaba’s investment in Paytm was by Alibaba Singapore Holdings Pvt. Ltd.

Chinese funding through entities located in other countries don’t get recorded in India’s FDI database as Chinese investments. Therefore, it will be interesting to observe how GoI prevents a takeover bid by a Chinese owned entity operating from Singapore or Mauritius. A report by Gateway House released in February 2020 suggested that “in several cases, the investment in India has not been made in the name of the Chinese entity/investor, and is, therefore, difficult to trace.”

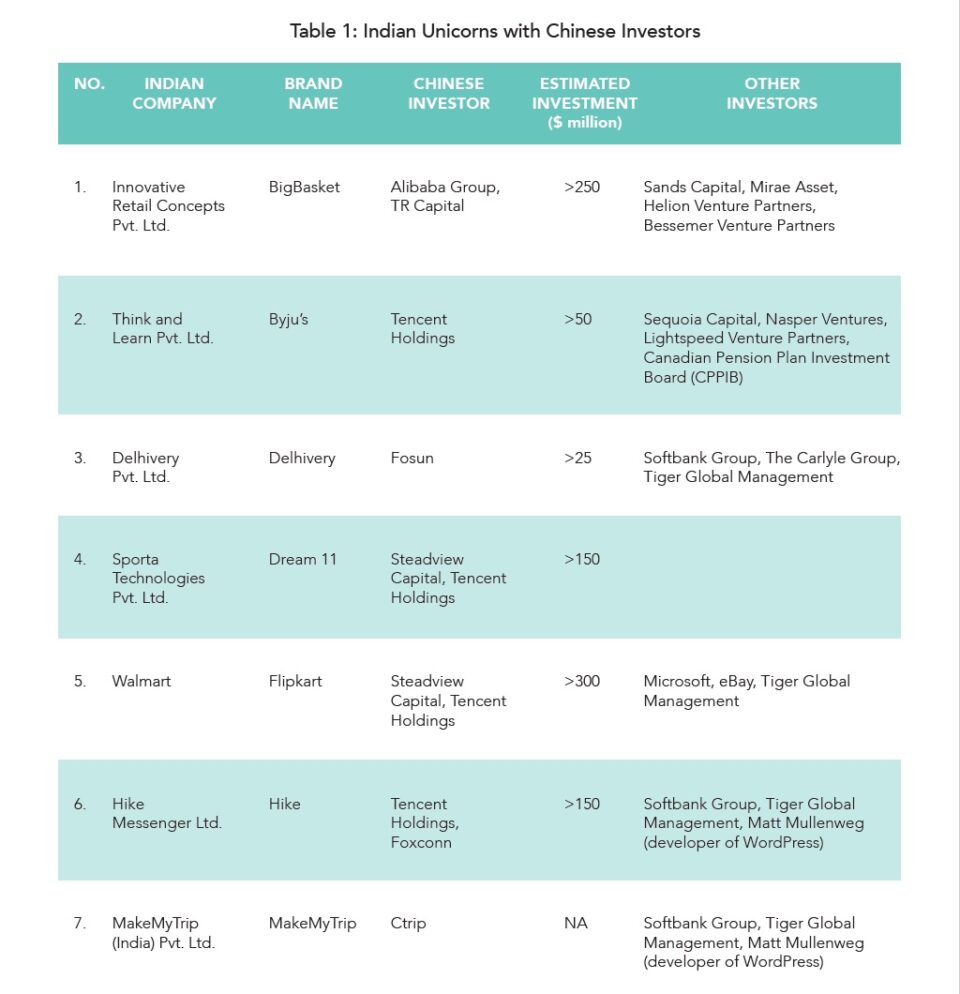

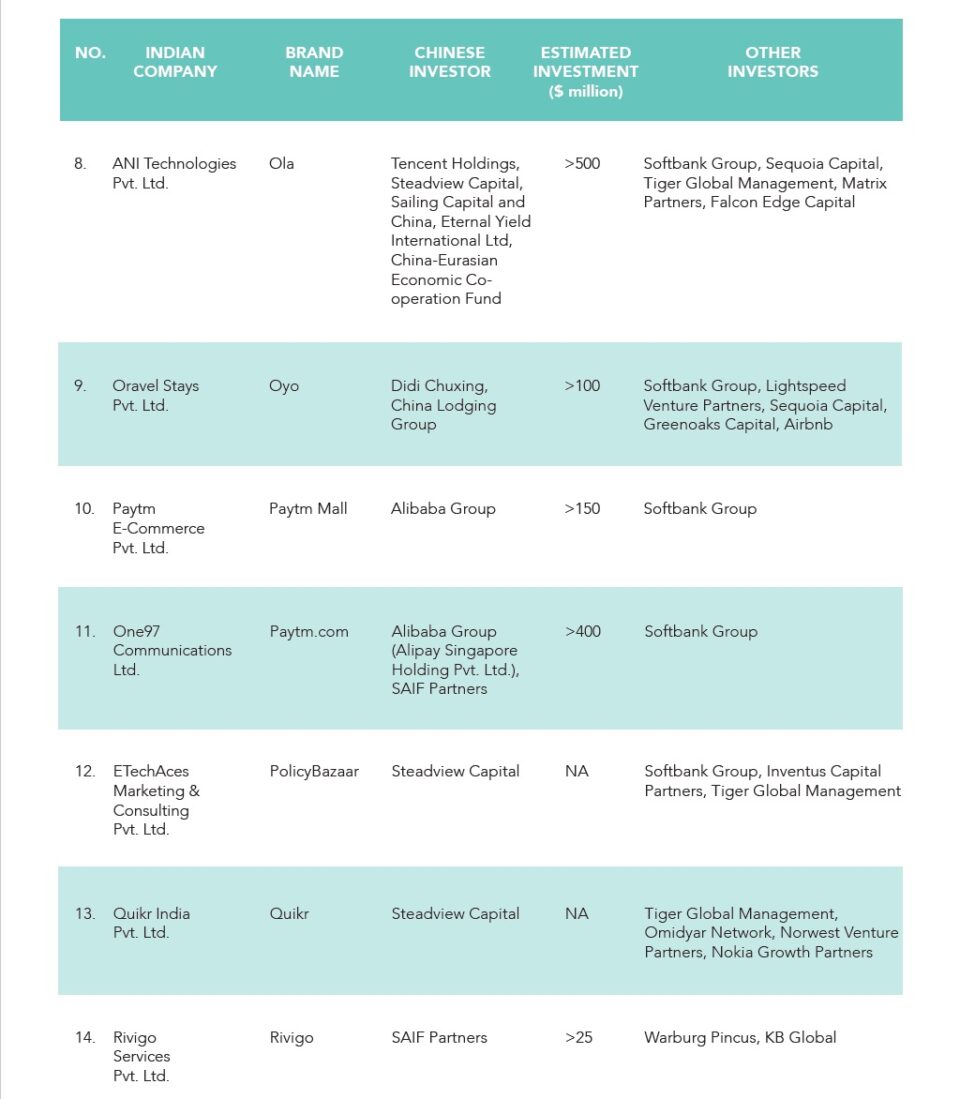

According to this report, “Chinese tech investors have put an estimated $4 billion into Indian start-ups. Such is their success that over the five years ending March 2020, 18 of India’s 30 unicorns are now Chinese-funded. TikTok, the video app, has 200 million subscribers and has overtaken YouTube in India. Alibaba, Tencent and ByteDance rival the U.S. penetration of Facebook, Amazon and Google in India. Chinese smartphones like Oppo and Xiaomi lead the Indian market with an estimated 72% share, leaving Samsung and Apple behind.”

Indian venture funders have been derelict in failing to understand the national imperative of funding an online/digital ecosystem that is fueled and driven by Indian funds and ownership. Their monumental failure to create depth of investing in the technology domain has opened this vital sector to Chinese investment led dominance.

The authors of the Gateway report point out that “China has taken early advantage of this gap. Alibaba’s 2015 investment in 40% of Paytm, a digital payments platform, paid off barely a year later when in November 2016, the government of India demonetised its large currency notes and simultaneously promoted a move to a cashless economy. Paytm benefitted from Alibaba’s superior fintech experience, which it applied to India seamlessly, making it a dominant player.”

“Second, China provides the patient capital needed to support the Indian start-ups, which like any other, are loss-making. The trade-off for market share is worthwhile. Third, for China, the huge Indian market has both retail and strategic value. Therefore, companies like Alibaba and Tencent have different considerations and horizons for their investments.”

The Digital Trojan Horse:

Are there are researchers or academic institutions working on finding out the shareholding pattern and Chinese investment routed through third-country entities? Who are these Chinese investors whose presence in Indian start-ups are overwhelming, but publicly unknown? What is their specific investment amount? The press releases and media positioning of these start-ups don’t give away these details.

They investment corridor China has built in India, through its entities located in other countries, has provided Chinese investors immense manoeuvring ability to open up new investment opportunities in India. One such opportunity is the shift to electric mobility, where China has expertise. “India is the world’s fifth-largest auto market; the sector is the country’s most robust and globalised export and it is a bellwether for the economy. China’s BYD has been pushing its electric buses in India, with limited success. In traditional autos, which is 99% of the market, China is using the recognisable, but distressed, global auto brands like Volvo and MG, which it acquired to enter the Indian market. So far, Chinese automakers have invested $575 million in India. The competition in India is fierce, and it’s with Indian and Asian automakers like Suzuki, Hyundai and Toyota, even as U.S. automakers withdraw.”

The impact of Chinese FDI in India – currently $6.2 billion – is enormous relative to the overall small amount, compared to the massive Chinese investment on infrastructure in other emerging economies or in India’s neighbourhood. Chinese investments aren’t channelised to building roads, ports or railway lines in India as is the case in other countries.

The question that Indian strategists should be asking is – What advantage does the fuzzy Chinese investment in Indian technology start-ups give to the Chinese security establishment? It has enabled an invisible Chinese presence in Indian society by funding the technology ecosystem that influences it.

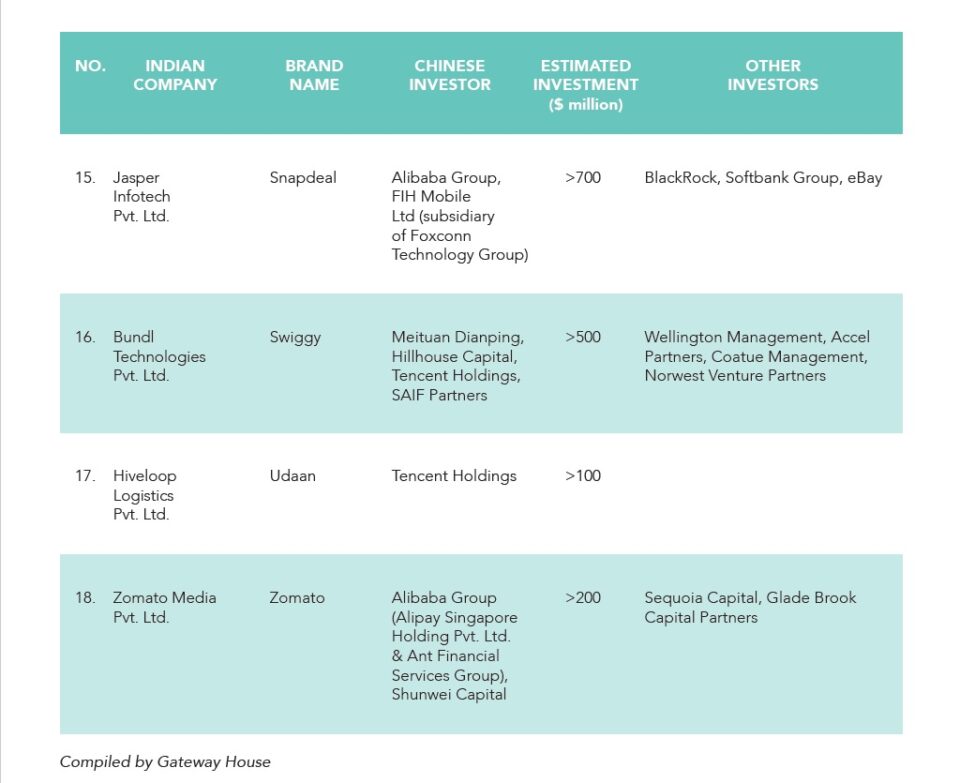

The Gateway House report has identified over 75 companies with Chinese investors concentrated in e-commerce, fintech, media/social media, aggregation services and logistics. A majority – more than half – of India’s 30 Indian unicorns (start-ups with valuation of over $1 billion) have a Chinese investor.

The average size of the Chinese venture funding in Indian start-ups is around $100 million. “These are investments made by nearly two dozen Chinese tech companies and funds, led by giants like Alibaba, ByteDance and Tencent which have funded 92 Indian start-ups, including unicorns such as Paytm, Byju’s, Oyo and Ola.”

The significant outliers are:

- $1.1 billion acquisition of Gland Pharma by Fosun in 2018 (this accounts for 17.7% of all Chinese FDI into India).

- There are five other investments by Chinese companies which exceed $100 million. This includes the $300-million investment by MG Motors.

Platform Control:

Reliance Industries, through Jio, is trying to replicate Alibaba’s successful model in India. With Facebook’s latest investment of almost $5.7 billion in Jio for just 10% stake, it is likely that that Reliance is aiming for Platform Control in India.

This is, perhaps, the first attempt by an Indian investor to take the challenge of Chinese opportunism headlong. Most Indian venture capital funds are either high or ultra-high net-worth individuals or family owned businesses. They either don’t have the capacity or the courage to make $100 million funding commitments to finance start-ups and see them through their early losses. For instance, Paytm incurred a loss of Rs 3,690 crore in FY193 while Flipkart lost Rs 3,837 crore over the year.

The Gateway House report distinguishes two kinds of Chinese investments.

- “Dedicated VC funds, such as CDH Investments, Hillhouse Capital, SAIF Partners and Ward Ferry, mostly based in Hong Kong. They are akin to professional global investors, such as Sequoia or Softbank, and look for financial returns.

- Tech companies, such as Alibaba, Tencent and Xiaomi (or their various arms), which want a serious presence in the Indian market, just as Walmart (via Flipkart) and Amazon do.”

“By restricting access to foreign players, China was able to create its own champions – which now rival the West’s. If Alibaba, Tencent and other Chinese tech majors replicate their internet ecosystems in India, this can create a systemic risk. An ecosystem such as this controls access to end-users; it means other companies (retailers, financing firms and media) will have to follow the standards/technologies prescribed to them. Alibaba/Tencent will be in a position like Google – they can decide which firm will succeed or fail by controlling user access, using their own technologies.”

There has been a lot of discourse on data security issues pertaining to Chinese investments in Indian technology sector. There is no clarity yet from the government on whether regulatory protocols are in place and whether it’s being followed by Indian start-ups with regard to loss of control over data. Given, that these are issues that have deep national security consequences as well as carry tremendous public interest, it is time that GoI put in place an elaborate data security policy.

(VK Shashikumar is an investigative journalist and a strategist. The opinions expressed by the author and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of Canary Trap or any employee thereof)

Note: We thank the authors of the Gateway House Report, February 2020 – Amit Bhadari, Blaise Fernandes, Aashna Agarwal – for their research on Chinese investments in India. This article has relied extensively on their research and has quoted significant portions of the article.

One Comment