Canary Trap presents an unconventional account of Kashmir by filmmaker and author Shiv Kunal Verma. The author of the highly acclaimed ‘1962: The War That Wasn’t’ and ‘The Long Road to Siachen: The Question Why’ takes us into the back alleys of history and based on established historical facts and his own personal experiences, he weaves together not just a picture of what has been happening in the disturbed state but also how things can and should pan out.

This is the third part of the series.

BY SHIV KUNAL VERMA

One of the questions that seems to haunt Indian academics and intellectuals in particular, to say nothing of the 1.3 billion multitude, is the identity of India itself. If a person from Kashmir or Nagaland today thumps his chest and says his or her identity has always been different, they fail to realise that the same can be said for almost every region in India, be it Bengal, Manipur, the Punjab, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Kerala or Odisha. In fact, the closer we are to our respective ground zeros in our individual capacity, the more divided we are. Caste, religion, languages, even colour—we happily “ekla chalo re” and let’s face it, we are also convinced that the others are absolutely loony!

Unfortunately, military geography as a subject or a concept is a completely alien thought in the minds of our people. Take a step back and move away from the narrow domestic walls that surround us and the picture of the whole that emerges, whether we are shouting from behind the barricades of JNU or from the madrasas of Deoband or the khaki clad marching columns of the RSS, is of a geographical entity called “India”. It is bound by the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal to the south, the wall of the Himalayas to the north, the Naga-Patkai chain of mountains to the east and the Hindu Kush range in the west. Within this huge cauldron of different geographical features and great river valleys, we are born and will die when our time comes—and during that period, we are all branded by the same brush as one people. As we near 75 years of Independence, perhaps we should start getting used to this idea.

When the first British warships arrived off Surat in 1612, the Portuguese and the French and the Dutch had already reached “India” a hundred and fourteen years before that. The flourishing markets of the Malabar Coast, where the Hindu Zamorins of Calicut ruled and commanded the seas with their Muhammadan admirals, frankly made the Europeans look like barbarians despite all their trappings. Even after the British arrived, for another century and a half, none of these so-called European powers could establish a foothold, until of course as so often has been the case in our history, the gates were opened from within at Plassey. This one act of treachery, in a far-away battlefield in the dusty Gangetic belt, saw the rest of the subcontinent collapse like a house of cards and the subcontinent was colonialised for the next two hundred years. No one escaped the yoke—be it the Christians, the Zoroastrians, the Jews, the Tamils, the Biharis, the Gujaratis or the Kashmiris.

My generation—born in the 1960s, was repeatedly told, the British “conquered” us by adopting a “divide and rule” policy. How many pencils have snapped in classrooms when teacher after teacher has used it as an example of how easy it is to break the one individual as against the collective whole. We listened, starry-eyed, for we were also told that history was important because we must learn from it and never make the same mistake again. But what we were not told—perhaps because none of our people realised it—that even though the British left in 1947, they put into place a final diabolical plan that even today continues to rip our soul apart, turns brother against brother, and leaves us as a race fighting a perennial war that actually never should have happened. Unless we look into the mirror of time, put aside all other compulsive arguments that start with the word “but”, we frankly do not stand a chance. The greed for power, their own vested interests having taken over the narrative somewhere along the way, continues to propel us forward. Just as a single cog at Plassey led to a collapse, until the embers of Kashmir and other such similar “hot spots” are not extinguished, we will continue to remain a fractured entity.

The British on their part always looked at India as India. The Indic identity existed long before they came and though over time the physical boundaries of Empires of yore shifted this way and that, they were in essence only political lines that have no meaning in the annals of time. The concept of modern day “frontiers” was introduced for the first time by Lord Curzon when he was the Viceroy of India between 1898 and 1911, and in keeping with his thought process, various expeditions were launched such as the ones undertaken by Captains Morshead and Bailey which in 1914 became the scientific bases of delineating the boundary between India and Tibet.

In 1991, along with Lieutenant General Adi Meherji Sethna and Dipti Bhalla we were discussing doing a series of historical films with Rajiv Gandhi on the Indian Armed Forces. Though he had lost the India’s Prime Ministership to V.P. Singh two years before, Gandhi was widely expected to be elected back to power later that year. The former Prime Minister seemed to have been fairly well briefed about the synopsis that we had sent to him earlier, but my remark that we wanted to start the series from 1919 had his complete interest… “We don’t have any documentary proof as yet, Sir, but we have reason to believe that the India Office had actually prepared a detailed plan for the partition of India into three separate states—Hindustan, Pakistan and Princesstan. I don’t think they were serious about the Princesstan bit, but had included it as a bargaining chip to counter any opposition from the Congress Party to make Pakistan a reality.”

I was referring to the plan drawn up in 1919, where in conjunction with the Colonial Office, the Admiralty, MI5 and MI6, the India Office was tasked with the preparing of a blueprint that would protect British strategic interests on the subcontinent with regards to the oil fields in Persia and the Middle East. Working on a strategy that took into consideration an 1857-like scenario where a massive uprising would force the British to leave the subcontinent, the plan was prepared wherein India would be divided into three parts. This was submitted to the House of Commons, but it was rejected. In the meantime, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre happened, and the British evoked the Rowlatt Act and talk of Home Rule just fizzled out. However, the seeds of creating Pakistan primarily to serve British interests in West Asia and to counter the Russian threat from the direction of the Parmirs had been created, and it became the unofficial document that influenced events thereafter.

“The concept of a Muslim state was first advocated by Iqbal in 1930. The very word—Pakistan—only came into play three years later,” General Sethna had added, “it was first mentioned by Rahmat Ali in 1933.” Then, much to our collective amazement, Gandhi said, “The document you are talking about was indeed prepared at that time and it was declassified some years ago. I have it here.” Unfortunately, though we were to meet again to take the discussion forward, Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated by the Tamil Tigers at Sriperumbudur while attending a public meeting. With him went our dream of making that document public.

The fate of India—and that of Kashmir—had been sealed in 1919 itself. Apart from wanting to retain control over the oil fields, the British plan to divide the subcontinent was also influenced by the Great Game that obsessed British military thought extensively. Kashmir’s remoteness over the years had hidden its strategic importance from the eyes of most Indian leaders, who in any case had far more immediate problems to deal with than to think of geopolitical issues.

The famed overland trading route, the Silk Road, was to Kashmir’s north. Linking Central Asia with China by way of Tibet this route was well worn by successive caravans and conquering armies some of whom included the Kashmir Valley in their grand designs. The state of Jammu and Kashmir was the largest and one of the most populous of the 562 principalities which dotted the map of India prior to the partition in 1947. It comprised an area of 84,471 square miles. Like most of the princely states during the British period, Kashmir was characterised by absolute autocracy in its internal affairs and a predominantly agrarian economy with a high concentration of land ownership. It had a constitutional status, encompassed in the doctrine of paramountcy, which acknowledged British suzerainty in all matters pertaining to defence, foreign affairs and communications, in exchange for a large measure of internal autonomy.

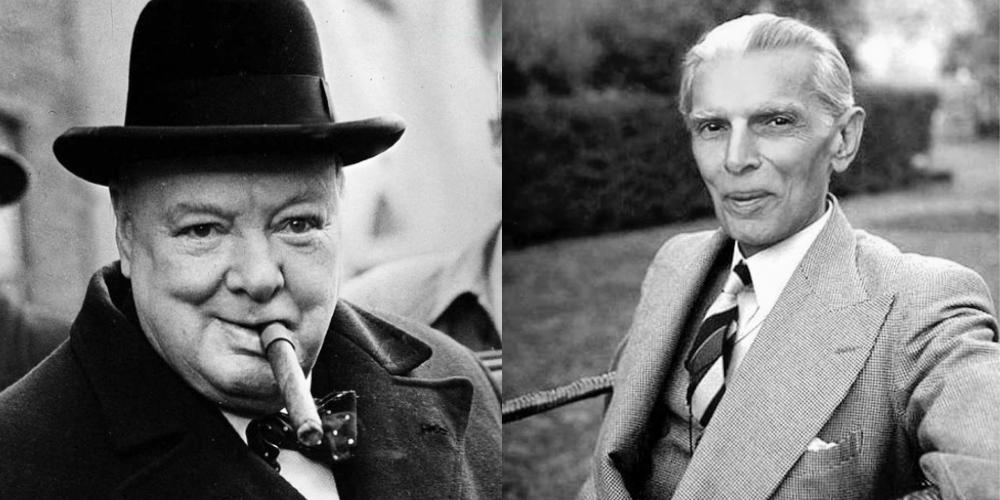

The India Office plan of 1919, despite being officially junked, had a natural supporter in one of the greatest champions of colonialism, and ironically the man at the helm of affairs when the Empire finally began to unravel, Winston Churchill. In October 1929, when Lord Irwin, the Viceroy, suggested Dominion Status for India, Churchill led protests in London calling the idea “not only fantastic in itself but criminally mischievous in its effects” and called upon his countrymen to marshal “the sober and resolute forces of the British Empire” against the granting of self-government to India. Over the next two years, Churchill delivered dozens of speeches where he worked up, in the most un-sober form, the forces hostile to the winning of political independence by people with brown or black skins.

Lest we dismiss Churchill’s outburst as that of an out of office politician at that time, it is worth recalling some of his other utterances about Indians in general. During the war years, Leopold Charles Amery, a contemporary of Churchill from Harrow, was the Secretary of State for India. Despite the fact that the fate of the subcontinent had been a keen issue of dispute between Churchill and Amery for many years, the Amery diaries underline the British Premier’s stance on India in no uncertain terms. In March 1941, when Amery expressed his anxiety about the growing cleavage between Muslims and Hindus in India, Churchill at once said: “Oh, but that is all to the good” because it would help the British stay a while longer. Further, in September 1942, quoting Churchill, the Amery diary reads: “I hate Indians. They are a beastly people with a beastly religion.” A year later, when the question of grain being sent to the victims of the Bengal famine came up in a Cabinet meeting, Churchill intervened with a “flourish on Indians breeding like rabbits and being paid a million a day by us for doing nothing by us about the war”.

The National Archives of Pakistan had also brought out the first series of Jinnah papers comprising two volumes in three parts. Dr I.H. Qureshi, sometime Professor of History at St. Stephens, and later Vice-Chancellor, Karachi University, confirms that Winston Churchill was closely in touch with Jinnah since the early 1930s and had done the initial spadework to accept the Partition plan. Historians had wondered who Elizabeth Gilliat was whom Jinnah was writing to on a fairly regular basis. For long it was thought that it was a fictitious name that Churchill had adopted. However, Elizabeth Gilliat was Churchill’s Secretary. As Churchill’s rival, Clement Attlee sought to hurriedly transfer power, Churchill was playing counsellor to Jinnah privately. He advised Jinnah that they should not be seen together in public while all correspondence should be addressed to “Miss E.A. Gilliatt, 6 Westminster Gardens, London”.

The “moth eaten-Pakistan” that Jinnah eventually got (the reference chiefly being to not having the entire state of Jammu and Kashmir under Pakistan’s control after Independence), suggests that larger plans and promises had been made. Even when Jinnah was adopting dilatory tactics in accepting the Partition plan as he was opposed to the partition of Punjab and Bengal, Churchill had sent a message which Mountbatten had conveyed to Jinnah that all British troops would be taken away from India, if Jinnah didn’t accept the Partition plan. Churchill had added, “By God, Jinnah is the only man who can’t do without British help”.

A hundred years have passed since the diabolical plan to split India was first conceived and tabled, and yet successive generations in both India and Pakistan, and in Kashmir, have failed to see the truth for what it is. If anything, the divisions that never existed on the ground a century ago today feel like deep schisms that are perhaps unsurmountable. To think that Churchill, an ex-Prime Minister himself, was acting on his own would be naivety in the extreme. In all probability, MI5, MI6 and just about every other British policy-making group would have been involved, for it was a matter of protecting British interests on the Indian subcontinent. That British interests later morphed into US and Chinese interests in subsequent years is altogether a different story, but the generations of today must dig deep into history to realise that this endless war (there simply cannot be another word for it) was never an India-Pakistan issue. The Anglo-Saxon bandmasters have perhaps long gone, but unfortunately their place has been taken by small men on all sides of the border who have continued to play the Game. The pawns, tragically, are you and me!

(This piece was first published on Sunday Guardian website. Canary Trap has republished it with the permission of the author Shiv Kunal Verma. Verma is the author of the books ‘The Long Road to Siachen: The Question Why’ and ‘1962: The War That Wasn’t’. The opinions expressed by the author and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of Canary Trap or any employee thereof)

Canary Trap is on Telegram. Click here to join CT's Telegram channel and stay updated with insightful and in-depth content on Security, Intelligence, Politics, and Tech.