BY VK SHASHIKUMAR

On a cold, cloudy windy Wednesday I called ‘The Week’ magazine copy desk from an Indian Army telephone booth in Dras to inform them that I would be on my way to Leh later that night to file the cover story. It was July 7, 1999 and I was just doing the last round-up of talking to army officials, soldiers and locals before getting onto a hired Maruti Gypsy. The copy desk told me – “We will send a confirmation message to the reception desk of the hotel in Leh after we receive your faxed story. Oh! And by the way – the war is over!”

From the day I arrived in the Kargil sector somewhere during the third week of May 1999, all days of the week were uncertain, except for Wednesdays. The Week magazine “went to bed” on Thursday and this meant that I had to file my stories by Wednesday late night/Thursday early morning. And it was equally important to do so without really missing any piece of action. Although this was an impossibility because the Kargil War frontage was approximately 160 km along the Line of Control between India and Pakistan and there was action happening everywhere – from Dras to Turtok.

But navigating through the narrow Himalayan Roads, choked with Indian Army trucks, heavy towed artillery and all kind of supply trucks and armoured vehicles was a challenge in itself. Besides, the road distances in mountains are not the same as straight line distance. For instance, on the map the Dras and Turtok are close to each other as the crow flies, but the road distance is a little more than 400kms and it takes nearly 15 hours to reach if one travels by car. So, it was impossible to be at several locations across the war zone in a day.

After the first week in the Kargil war zone, I evolved a strategy that was a perfect fit for me as magazine reporter. Every Wednesday morning, I would start from Hotel Kargil with a bag packed for a week. I would connect with my army contacts in Kargil, then drive down to Dras, stopping on the way if I spotted army convoys or supply trucks halted for a breather. They were always a great source of information. In Dras, where a lot of military action was concentrated, I would meet soldiers and officers who had returned from an assault or were preparing to move on a combat mission. This would give me a good sense of what’s about to unfold.

On July 7, 1999 as the cold chill of the evening set in – Dras one of the coldest places on Earth was quite cold even in July – I hopped into the Maruti Gypsy to drive back to Kargil and carry onwards to Leh, non-stop. This was the routine every Wednesday. During 8 to 9 hours of drive to Leh, covering 280 kms, I would pour my notes, figure out the outline of the report and make plans for the week ahead. As soon as I reached Leh in the early hours of Thursday, I would begin writing the report (story) on plain A4 paper after checking into a hotel. By 8 am I would be waiting at the front office of the Hotel to fax the story to the magazine’s copy desk. Meanwhile, my photographer colleague would figure out transmitting the photographs from an internet café. The connectivity was patchy, and journalists then weren’t equipped with laptops or smartphone. Only two media organizations had satellite phones – Indian Express and NDTV.

Before noon, every Thursday we would have transmitted our report and photographs and after a quick lunch at Leh, we would be ready to set out back into war zone. On the way back we would drive down from Leh and instead of joining continuing on NH1 we would veer off right towards Batalik and Turtok to check on developments there and after spending two days and nights in the open, reach Kargil on Saturday morning.

After a quick shower, change of clothes, head out a bag full of fresh clothes. Journalists who were stationed in the war zone, called this “the Chakkar”. Everyone had a Chakkar routine, which ensured that they had covered all these regions in a week – Dras, Kargil, Batalik and Turtok. Saturday would be in and around Kargil and Sunday to Tuesday would be spent along the 65 km Kargil – Dras stretch, where a lot of the war action was happening. We often slept in the car and ate in army langars along the road.

The story I was covering, like all the other journalists, was about a surreptitious Pakistani intrusion into Indian territory. During the winter months of late 1998 and early 1999 the Pakistani army had infiltrated 4 km to 10 km inside Indian territory and occupied 130 Indian army high altitude posts. These posts at the height of 14,000 ft to 18,000 ft are inhospitable during winters because they are snow-bound, movement is difficult and dangerous and with sub-zero temperatures. So, the Indian army practice was to vacate these 130 posts during winters and re-occupy them as soon as the winter months got over. But on May 3, 1999 local shepherds informed the 56 Mountain Brigade in Dras that they had spotted Pakistani soldiers on the ridge line and in the posts vacated by the Indian army. This is how Kargil War started – quietly, without any drama.

This is how it ended as well. Quietly, without any drama and without anyone in the war zone really knowing about it. That’s why July 7, 1999 is such a weird date for me. At the war zone – the army units, the local civilians and people like us (journalists) – had no clue what was happening outside. We did not know Nawaz Sharif had met Bill Clinton on July 5, 1999 and had agreed to stop the war. Even though the Pakistani army announced its withdrawal on July 11 and India declared Operation Vijay a triumphant success on July 14 and officially the Kargil War ended on July 26, 1999, the fact of the matter is that war continued. In fact, the last story I filed for the issue dedicated to Independence Day was on how Indian and Pakistani troops were jostling for occupying some of the strategic mountain heights in the war zone. Of course, eventually India army did achieve “Poorna Vijay” and evicted Pakistani army from all the heights except these four contentious posts – Point 5353, Bunker Ridge, Saddle Ridge and Dalu Nag, which till date continues to be controversial and covered by the fog of war.

The fog of war in the digital age has become more complex. The narrative of the government often does not match with the evidence provided by Satellite imagery provided by the high resolution cameras mounted on Satellites orbiting the Earth. If Pakistani armed forces were to mount an operation like Operation Badr now, in the digital age, to capture the mountain heights along the LoC, they would be exposed by Open Source Intelligence Platforms (OSINTS) within seconds.

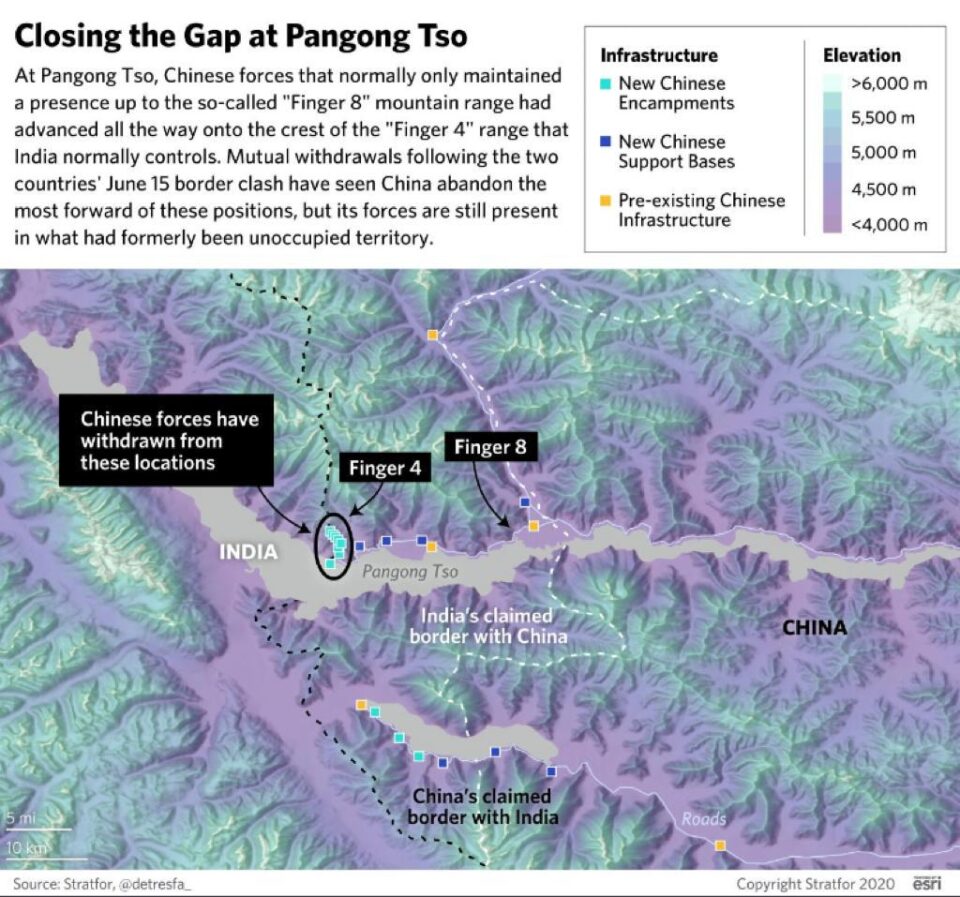

For instance, an OSINT twitter handle – @detresfa_ has issued warnings since last year that China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) was steadily building up its men, material and resources along the Line of Actual Control (LAC). Especially in the Galwan Valley area and Pangong Tso lake in Ladakh after securing total control over Doklam Plateau at the trijunction of Bhutan, India and China in 2017. The latest satellite pictures shared on several OSINT platforms show that while Chinese troops have disengaged and moved at least 2kms back from the India-China clash points, there is an ongoing and steady build-up of Chinese army infrastructure beyond its LAC buffer zone.

On the LAC the buffer zone averages 9 kms on Indian and Chinese sides. There are some points along the 3,488 km long LAC where the buffer zone on either side stretches to 11 kms and sometimes to even 20 kms. Historically, given that the LAC itself is heavily contested in the Western and Eastern sectors by India and China, incursions by Indian and Chinese army patrols have been a regular affair as both sides try to maintain their territorial presence along the disputed and unsettled border. However, since the 1990s the Chinese embarked on a focused strategy of incremental advancement and land grab in an effort to close out the buffer gap on the Indian side of LAC.

China’s effort to grab and occupy LAC buffer zone on the Indian side has been more aggressive since 2014. After the 90-days 2017 Doklam stand-off the Chinese strategy has been to fortify its side of the LAC and try to strategically close out the buffer zone on the Indian side of the LAC. For instance, a 1960 report by Ministry of External Affairs, “Report of the Officials of the Government of India and the People’s Republic of China on the Boundary Question” indicate the India’s claim line started at Finger 8 area of Pangong Tso lake, while China contested its claim line at Finger 4. Traditionally, India would send long range patrols till Finger 4 and claimed an 8km buffer zone till Finger 8.

By occupying areas in Pangong Tso lake region till Finger 4, China’s PLA has effectively taken over India’s buffer zone territory and reduced its claim line by 8 km from what it was in 1960.

There is another matter that is hardly occupying any media attention. The entire focus is on Chinese occupying the Indian side of LAC on the ground, but what about the mountain tops. In mountain warfare, especially in the Himalayas, those who occupy the heights eventually control the battle. That is why India’s victory in the Kargil War is so significant. This was one of the toughest mountain warfare anywhere in the world and the Indian army had to climb steep mountains to defeat the fortified Pakistani army positions on mountain tops. General Pervez Musharraf’s plan was to cut off India from Kargil by dominating the mountain heights and not allowing any Indian army movements on NH1, thereby severing connectivity.

Similarly, what are the intentions of the Chinese PLA units camped in posts along the ridge line of Galwan heights? Though the PLA units have withdrawn 2 kms on the ground, there is no talk about their withdrawal from the ridge lines and mountain tops. In the digital age there will be no place to hide. Now we don’t need shepherds to inform Indian army that intruders have come into Indian held territory. There’s an army of open source intelligence enthusiasts who use accurate satellite imagery to pour over every inch of land, water and air. These satellite images, available in the public domain, clearly prove that China is occupying the Indian side of the LAC buffer zone in Galwan Valley and Pangong Tso lake region. However, what we don’t know yet is whether like the Pakistani army, the Chinese PLA has made fortified posts on top of the Galwan Heights.

(VK Shashikumar is an investigative journalist and a strategist. He covered the Kargil War for The Week magazine. He is now a systems strategist and writes occasionally on defence and strategic affairs. The opinions expressed by the author and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of Canary Trap or any employee thereof)

This piece first appeared in Sangbad Paridin newspaper and has been republished here with the permission of the author.

Canary Trap is on Telegram. Click here to join CT’s Telegram channel and stay updated with insightful and in-depth content on Security, Intelligence, Politics, and Tech.